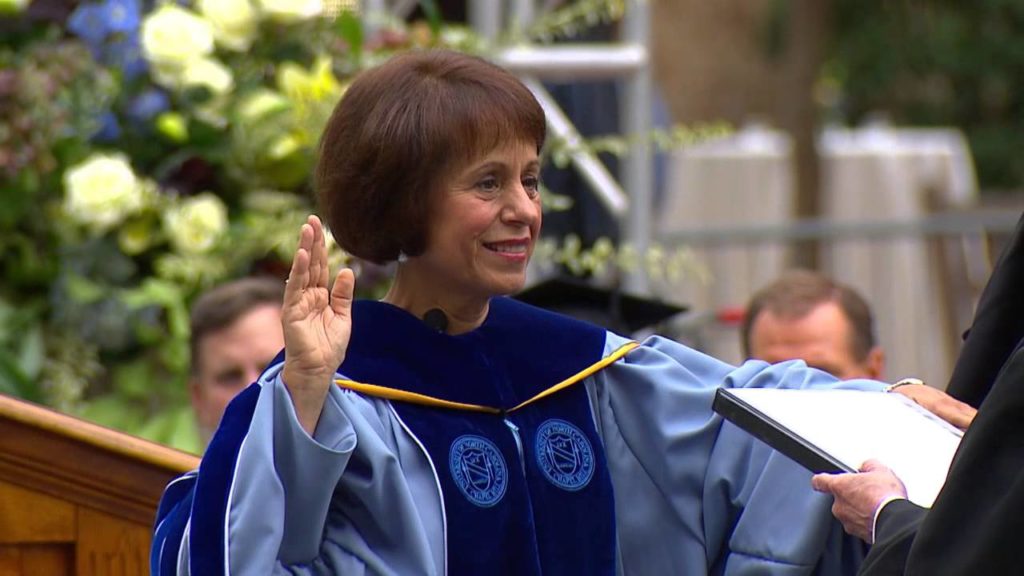

NExternal calls for accountability, political attacks on faculty members, the decline of tenure-track positions — the reality for faculty today is as challenging as at any time in recent memory. Add to these factors the ratcheting up of research expectations, teaching loads, service obligations and administrative requests, and how can we possible expect faculty to get everything done?

Reflecting on the current state of higher education, Nobel laureate Peter Higgs said, “It’s difficult to imagine how I would ever have enough peace and quiet in the present sort of climate to do what I did in 1964.” The time pressures on faculty members — and particularly pretenure faculty members — are much higher than previous generations faced.

As a result, faculty members have to manage daily demands as well as long-term priorities in order to succeed. While we need a system for managing our calendar and to-do list, we also need a renewed focus by both senior faculty members and administrators on the work that matters most. In the absence of a larger institutional focus, each of us has to take charge of our careers and make sure we are doing that work.

Indeed, we should focus less on how to improve efficiency and more about what faculty members are actually doing. Productivity tips and tricks can be helpful, and I often encourage my colleagues to try new approaches or software solutions to save time. But efficiency for efficiency’s sake or to free up time for administrivia is pointless.

Greg McKeown, the author and business consultant, suggests that productivity is often about doing less, not more. McKeown argues that by doing less, we can spend time on work that really makes a difference. When I think about faculty work today, this idea, which can admittedly seem like a self-help trope, actually holds power to both reduce the constant feeling of busyness while also improving the quality of our work.

For example, what if you spent more time creating an interactive activity for class than revising the look of your lecture slides? What if you created an answer sheet with clear explanations to distribute to class rather than writing brief notes in the margin on each individual student exam? What if you checked your email three times a day instead of three times an hour? Think of the progress you could make on your highest-priority projects. There are countless examples, within our control, where we could decide to focus on creating value for our students or in our research endeavors rather than letting busywork take over our day, week and semester.

After his return to Apple, Steve Jobs significantly reduced the number of product lines sold by the company. Reflecting on his strategy in 1997, he said, “People think focus is just saying yes to the thing you got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully. I’m actually as proud of the things we haven’t done as the things I have done.”

So, how do you do this? First, you have to view time, at least to some degree, as a zero-sum game. You only have a fixed amount of it, which means when you say yes to something, you are also saying no to something else. If you agree to meet with a student group for an hour on Wednesday afternoon, that means saying no to an hour for research and writing. Saying yes to staying late for a committee meeting means saying no to your son’s baseball game.

One of the joys of faculty work is that we can find many intellectually stimulating and engaging opportunities to get involved on campus. A few people enjoy committee meetings, but advising students, leading research labs or writing an article or book are all aspects of our roles that brought us to the academy in the first place. Thus, you are rarely deciding between good and bad requests for your time, but good and better options.

We have to consider how the decisions regarding our time each day, week and semester shape our careers. For faculty members on the tenure clock, the ever-present anxiety to achieve tenure can be derailed by daily decisions to focus on things that do not help advance your tenure case. Of course, that does not mean you should never do something if it does not help your pursuit of tenure. But you will struggle if you do not prioritize the work that your institution and tenure committee value.

In the end, time is a zero-sum game that requires trade-offs. We all make these trade-offs every day, but often without thinking about it. Trade-offs exist in balancing professional work in teaching, research and service — as well as between our professional and personal lives.

The best way to tackle the zero-sum game and better prioritize our time is to make explicit the trade-offs that exist in faculty work. When a new request or opportunity presents itself, ask if it is something you want to pursue and what you would have to say no to or stop doing in order to say yes to the request.

For early-career faculty members, discuss with senior colleagues and mentors the trade-offs you face, and seek help in making these decisions. Administrators should consider the requests being made of faculty members and think about the trade-offs required to satisfy a new reporting requirement or change of software.

One of the worst things that can happen is that we justify the increased demands. “I have to work all the time, but only while I am on the tenure clock.” “I have to prioritize my research for this deadline, but then I will give attention to my teaching.” Such temporary justifications have a sneaky way of becoming permanent reality.

This essay first appeared in InsideHigherEd on February 7, 2019.