Although much of American politics today is frustrating and sad, I’ve been completely fascinated by the power transition occurring in the U.S. House of Representatives over the last few weeks. In particular, I have watched closely Paul Ryan’s role and change of position from I won’t run to I will if my demands are met. While I have fundamental political and policy disagreements with Representative Ryan, I have been quite impressed with how he has handled the situation roiling his caucus. In today’s post, I will share the four demands that Ryan had before agreeing to run for speaker and what Paul Ryan’s demands can teach higher ed administrators.

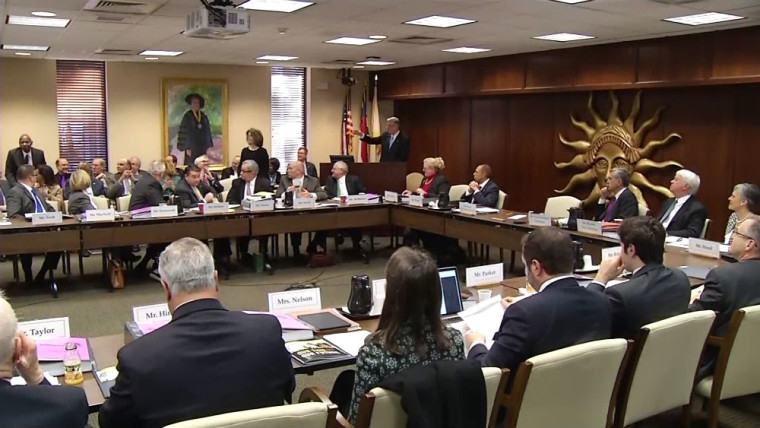

Photo credit: Getty Images

Almost immediately after John Boehner announced his resignation as speaker, Paul Ryan was suggested as a potential consensus candidate to bring together the Republican House caucus. Just as immediately, Ryan said he would not be a candidate. Over time, as no viable candidate came forward, Ryan softened his stance and said he would run if he could actually unify the party and if his conditions were met.

I found that situation remarkably similar to how many administrative positions in higher education are filled, particularly academic administration openings. Many faculty initially decline, but are eventually talked into accepting the post.