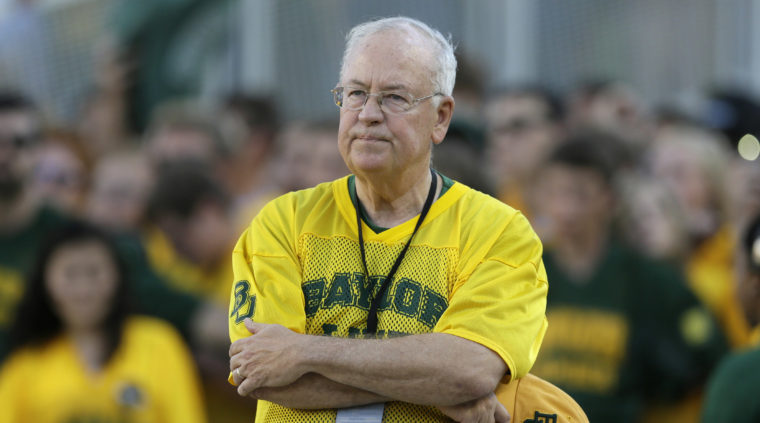

With the ongoing free speech debates, growth of student protest movements, and a general political disquiet in the nation, I’ve been thinking about how institutional leaders manage and guide their institutions during turbulent periods. This has made me think back to an article I wrote several years ago with Kenneth A. Shaw, the former chancellor of Syracuse University. In the piece that appeared in Trusteeship, we considered how to track emerging issues and grapple with public relations challenges. For today’s blog post, I want to share the article as it remains as instructive today as when we first wrote it in 2006.

Photo credit: The Daily Orange

Before All *@#%! Breaks Loose…

By Kenneth A. Shaw and Michael S. Harris

In helping your institution grapple with public-relations challenges, be prepared to track emerging issues through four distinct stages.

IN SEPTEMBER 2005, Education Secretary Margaret Spellings announced the formation of the Commission on the Future of Higher Education. But many knowledgeable observers reacted with surprise. Why was the secretary acting now? What is the purpose of the commission? Is the Bush administration pushing to implement a college version of the No Child Left Behind law?

Many of these questions will be answered as the commission completes its work this fall. Yet we know from the group’s membership and discussions to date that accountability is going to be a major theme of its recommendations. Trustees and chief executives need to ask why we were taken aback by creation of a major commission and what boards can do in response to this and other issues that arise nationally and on our campuses.

Part of the answer may lie in three words, “Just Do It.”