It has been a rough few weeks for college presidents. I recently spoke to Adam Harris from The Atlantic about the recent controversies surrounding college presidents and want to share his insightful article for today’s post.

Who Wants to be a College President? Probably not many qualified candidates.

By Adam Harris, The Atlantic

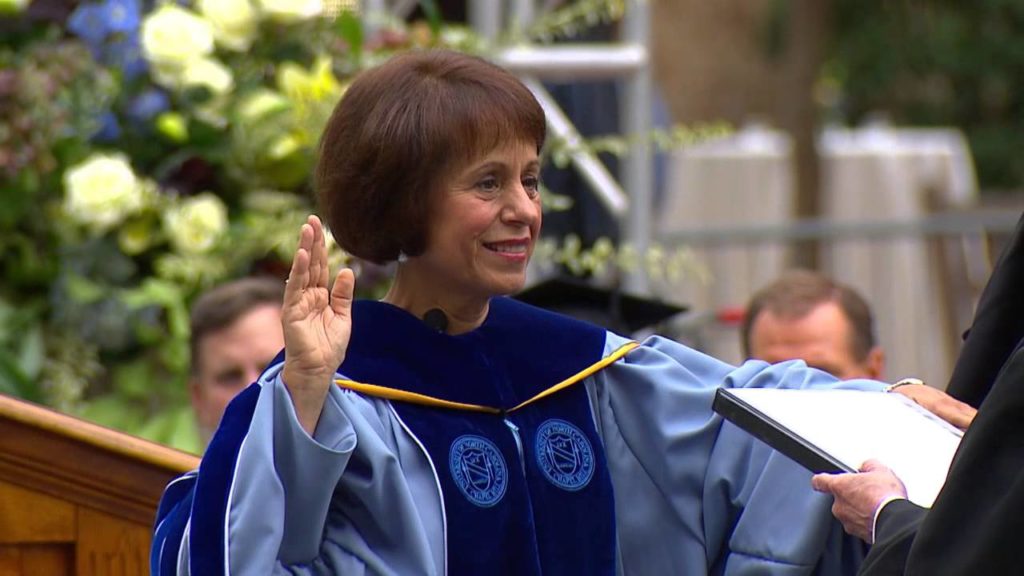

Carol Folt had to make a decision, and none of the options was great. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill chancellor was caught between a conservative Board of Governors that seemed to favor returning a monument of a Confederate soldier, known as Silent Sam, to the pedestal from which it had been yanked last fall and a student body that heavily favored its permanent removal. The stakes—her job, but also the security of UNC’s campus—were high.

In a letter to the campus community on January 14, Folt announced that she’d made up her mind. She’d be stepping down at the end of the semester, and she’d be taking down what was left of Silent Sam, immediately. “The presence of the remaining parts of the monument on campus poses a continuing threat both to the personal safety and well-being of our community and to our ability to provide a stable, productive educational environment,” she wrote. “No one learns at their best when they feel unsafe.”R

Folt’s choice highlights the tightrope that university leaders walk between ideologically driven boards and their campus constituencies. “When you get right down to it, the relationship with the board—and the extent to which the board is separate from campus, and doesn’t necessarily have a full appreciation for the different views that may exist on campus—that disconnect puts presidents in an incredibly difficult position,” Michael Harris, a professor at Southern Methodist University who has studied the turnover of college presidents, told me. That difficult position may be one that fewer qualified candidates for college leadership are choosing to take. One survey noted that in the past decade, more current college presidents have been sidestepping the traditional pathways to leadership and, anecdotally, even some of those nontraditional candidates have turned down potentially tumultuous positions. But if leaders with higher-education experience won’t do the job, who will?

The Board of Governors was, predictably, furious with Folt’s decision. “We are incredibly disappointed at this intentional action,” Harry Smith, the board’s chair, said in a statement. “It lacks transparency and it undermines and insults the Board’s goal to operate with class and dignity.” The board met the next day and accepted Folt’s resignation, but not effective at the end of the semester. Instead they gave her two weeks.

The accelerated ouster was the culmination of years-long tension at the university between the ideologically conservative board and university leaders. Margaret Spellings, the president of the UNC system, who announced she’d be resigning this year as well, had her own tensions with the board, including over her decision to ask the state governor for help in deciding Silent Sam’s fate. She had been hired after Tom Ross, the former system president, was himself forced out by the board in 2016. The rapid cycle of hiring, resignation, and removal creates a problem for the university. “I don’t know who would want that job right now, given the board and its ideology. And I worry about who they would find palatable enough to put in the position,” Harris told me. “One of the great university systems, and one of the great universities, is going to be damaged by this process.”

That tension between a college’s board and its president isn’t one exclusive to the UNC system. A few years ago, following a string of athletic scandals, Harris wanted to know whether more college presidents had been fired in recent years—or whether they had their resignation accepted on an accelerated schedule. Two years ago, he and Molly Ellis, a graduate student, published what they had found. Yes, the study said, over the past two decades presidents had been getting fired more often. But the why was perhaps more interesting: Boards have always had the responsibility of “hiring and firing” a president, but “there’s a sense of activism among boards now,” Harris said. “Historically there has been a little more deference than boards are willing to give now.”

Of course, it isn’t just board oversight that could make the job of college president seem unappealing. Provosts, or even deans, who may have been groomed for the position might balk at the fundraising and politics associated with it. And these days, many open college presidencies come ready-made with crises. John Engler recently became the second president to leave Michigan State University in one year. The University of Oklahoma’s president, Jim Gallogly, is trying to navigate instances of racism at the institution, notably, a Snapchat video of students wearing blackface and saying the N word that went viral this month, which follows another racist viral video at the institution in 2015. There’s also an ongoing crisis at Baylor University, which is dealing with the fallout from a sexual-assault scandal.

“The number of qualified candidates is probably on the decline due to the job being less attractive, and I think we have boards trying to look for outside-the-box hires that more often than not don’t tend to work out,” Harris said. Those outside-the-box hires could look like Rex Tillerson, the former secretary of state, who was courted to be the next chancellor of the University of Texas system; or like Mick Mulvaney, Donald Trump’s acting chief of staff, who met with the University of South Carolina’s board before ultimately deciding that he was not interested in the position of president.

A board has a responsibility to a university, one that can be corrupted when political ideologies are introduced, Harris said. “That fundamentally damages a university, and that can take generations to recover from,” he said. He pointed to the damage that politics have done to the University of Wisconsin system as an example. It’s a public higher-education system that was admiredby the world, but it’s been hampered by controversy after budget cut after controversy over the past decade, and, in short, it’s suffering. It’s the kind of situation that UNC is hoping to avoid, but one that it, and other institutions, may be on a collision course toward as boards become more ideologically driven—and if qualified candidates continue to shy away from university leadership.