In higher education, we tend to want to study successful leaders. However, we can also learn a great deal from those leaders that end up not succeeding for whatever reason. Recently, my research assistant, Molly Ellis, and I published an article in the Journal of Higher Education on involuntary turnover among college presidents. In today’s post, I want to share the key conclusions and implications from our work.

This study examined the terms of university presidents, the causes for involuntary turnover, and how these two metrics have changed during 1988 to 2016. Our findings are largely consistent with existing empirical research on the challenges facing university presidents (Birnbaum, 1992; Eckel & Kezar, 2011; Martin & Samels, 2004; Padilla, 2004). Along with earlier work, this study strongly supports the complexity inherent in the modern university presidency as well as the competing demands presidents face. Our work reveals the most common reasons presidents at NCAA Division I universities are dismissed. Additionally, our research complements the work of scholars of the college presidency and adds an additional perspective to the ongoing debate regarding the college presidency and the escalating challenges and complexities facing presidents today (Eckel & Kezar, 2011).

One of our major findings was that, among our sample, the number of years that a president had served in a given year was largely unchanged during 1988 to 2016. By considering the numbers of years that a president served as of a given year, we were able to consider presidential longevity more accurately than only being able to calculate an average at the end of a president’s term. Given the sample size, average length of term becomes a problematic measure vulnerable to substantial fluctuation by noise in the data. Public university presidents’ average completed tenure was shorter than their private counterparts, but these differences were largely consistent during the time period.

Instead, the most dramatic change was the recent rise in the number of involuntary turnovers. More than half the involuntary turnovers that we identified occurred in the post-2008 period as they increased across almost all the categories and demonstrated the diverse pressures on modern-day presidents. These challenges extended beyond financial considerations to imply concerns about commercialization (Bok, 2003), politicization of higher education (Mettler, 2014), public mission (Marginson, 2011), and external pressure on institutions (Bowen & McPherson, 2016). Although the discourse of competing demands on university presidents often tangentially references the difficulties facing presidents (ACE, 2012; Eckel & Kezar, 2016), our findings confirm that successfully ending a presidency is less likely now than at any time in recent history.

In examining presidential turnover, the causes of involuntary turnover can be similarly categorized across institutions via our conceptual framework, suggesting that turnover follows familiar patterns across organizations (Van Velsor & Leslie, 1995). In line with this framework, our data showed that presidents faced common causes of involuntary turnover despite vast differences in organizational culture and particular context. Thus, although the people, facts, and history of each

turnover differ, each case can be neatly categorized with causes comparable to those found in other industries. Van Velsor and Leslie’s (1995) work and our own suggest that institutions and presidents need to consider the causes of turnover to inform decision making.

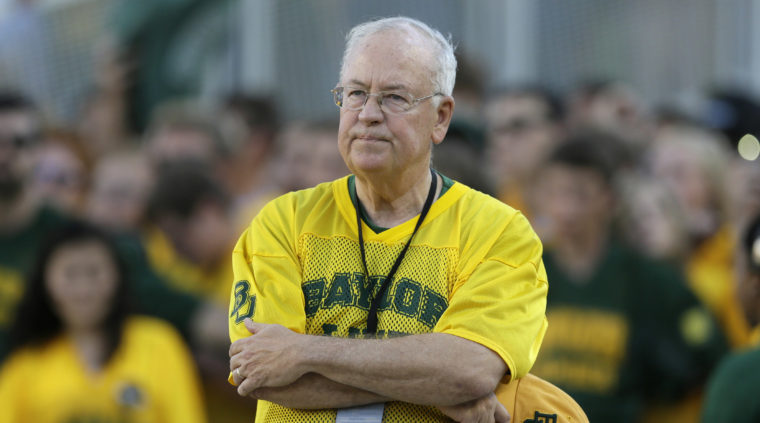

This study advances the number of presidencies ending in involuntary turnover as a preferable metric of the challenges facing presidents. Although measures of average term of office can provide some insight, the use of involuntary turnover provides a clearer picture of the challenges facing presidents today. Indeed, our data support the concerns raised by researchers and presidents themselves regarding the problems presidents confront and the impact on their longevity in office. College presidents, similar to chief executives in other fields, must manage challenges that can bring about derailment. Van Velsor and Leslie’s (1995) framework and our data show that common derailment factors exist across institutions. In addition, our findings provide empirical data to demonstrate that popular perceptions about the causes of presidential turnover are unfounded, including the notion that athletics scandals present challenges that are among the most common causes of involuntary turnovers. Managing Division I athletics presents a great challenge for many presidents (Kiley, 2012; Nocera, 2013), and athletics controversies have recently impacted several high-profile universities (Penn State, Ohio State, North Carolina, etc.). However, the number of these incidents has not escalated as dramatically as popular rhetoric contends. Rather, involuntary turnover has increased across the range of categories identified in this study. While simple athletics controversies may resonate more in the public consciousness than poor fit, judgment, or loss of board confidence due to the media coverage of athletics (Kiley, 2013a), a broader conceptualization of causes for involuntary turnover is paramount to draw a full picture of a president’s term, challenges, and success.

Implications for practice

This study argued that the challenges facing presidents are escalating and culminated in more frequent involuntary turnover in recent years. Indeed, while no single cause accounted for the increase in involuntary turnover, our data demonstrated how a range of presidential challenges are now more likely to end a presidency. The modern university presidency presents a proverbial minefield that future and current presidents must survive. The hierarchical power and legitimacy of their roles magnifies many presidential decisions (Birnbaum, 1992), while presidents are also buffeted by external events that may dramatically influence their power and decisions, as well as the perceptions of various stakeholders (Birnbaum & Eckel, 2005; Meyer & Scott, 1983). As if these challenges were not enough, presidents must also lead institutions in the face of significant pressures confronting higher education as a whole (Brewer et al., 2002; Eckel & Kezar, 2011; Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004).

The implications of our study for presidents are many. Although presidents undoubtedly have some understanding of the challenges they face, our data provide evidence of the issues that most often lead to involuntary turnover. Presidents of course have limited ability to influence external events, but we believe our data can provide useful to navigating those issues that remain in their control. One of our recommendations is that presidents take special care in responding to the issues outlined here because of their job-ending potential. Moreover, presidents should foster relationships with board members and the campus community to build social currency that may temper crises occurring during the normal life of an institution.

Beyond these recommendations, our analysis of involuntary turnovers since 2008 holds additional importance for presidents. Because the Great Recession of 2008 caused substantial funding challenges for higher education institutions, including state funding decreases and changing cost shares (Barr & Turner, 2013), one might have expected an increase in involuntary turnover related to issues of finance. In contrast, the category of financial controversies was the only category in which more involuntary turnovers occurred before 2008. Thus, our findings suggest that something beyond financial issues occurred in these institutions. To examine this aspect of our analysis in more detail, we return to the theories frequently used in the literature related to derailment and presidential turnover. Our data suggest that both of the primary research traditions for CEO turnover may have utility in examining involuntary turnover among university presidents in the wake of the Great Recession.

In particular, we believe that factors of organizational context can aid our understanding of involuntary turnover. For example, why does a particular crisis or controversy lead to one president’s departure while another president facing the same issue remains in office? The literature examining organizational performance (Hotchkiss, 1995) and organizational characteristics (Becker- Blease, Elkinawy, Hoag, & Slater, 2016) may offer useful conceptualizations of this issue, but more research in these areas would help further frame the organizational context of presidential tenure. Our view of the data leads us to believe that press coverage may play a substantial role in how campus constituencies view a president, especially in times of crisis; inquiries along this line could echo the work of Farrell and Whidbee (2002).

Organizational context provides a critical theoretical approach to helping researchers understand the larger themes and trends related to involuntary turnover. However, this tradition fails to fully capture the variety of challenges that we found in our data. For this study, we did not consider if causes for turnover were appropriate or even necessary. The theoretical research on ritual scapegoating, for instance, proves quite useful for evaluating involuntary turnover as a symbolic activity (Gamson & Scotch, 1964) for either internal or external constituencies (Pfeffer, 1983). Several of the presidents that we identified as leaving because of involuntary turnover left or were forced out in an attempt to move the institution past a controversy. This finding would suggest that in at least some cases, the symbolic benefit of involuntary turnover was evidenced in our data.

Our study has implications for institutions and other institutional stakeholders. The interpersonal dimensions of the presidential search process must be considered. For example, five out of six involuntary turnovers for poor fit occurred after 2008. Once a president is hired, there is only so much that can be done about poor fit. University decision makers and most notably trustees should put far more time, effort, and attention into the search process to better identify potential fit issues prior to a new president’s arrival. Therefore, there is a need to further explore research on personal characteristics and behavior of presidents as noted by Leslie and Van Velsor (1996). In some instances, the presidential search process ought to be restructured to provide more opportunities for interaction and feedback among all campus constituencies. Presidential candidates also need to invest significant time and resources to ensure campus fit from their end. Of all the causes of involuntary turnover, poor fit may be the most damaging to the institution and president because of the rapid turnover and controversy that often occur. If due diligence could minimize its likelihood, presidents and boards would be well served to do everything in their power to ensure fit.

Based on our findings, we contend that trustees have a particular and under-examined role in impacting presidents’ success or failure. While prior research has considered trustee decision making in areas of evaluating presidential performance (Fisher, 1996; Michael, Schwartz, & Balraj, 2001), managing, policymaking, and decision making (Bok, 2003; Pusser & Turner, 2004), and composition and relationships (Pusser, Slaughter, & Thomas, 2006; Woodward, 2009), our study illuminated how boards should manage presidents and decision making. Selecting a president is considered one of the most significant roles of trustees (Chait, Holland, & Taylor, 1996; Plinske & Packard, 2010), but as noted in the discussion of poor fit, some involuntary turnovers are rooted in initial hiring decisions. Our findings suggest that a focus on potential causes of involuntary turnover during hiring may reduce turnover. Moreover, we identified board members as significant players in several causes for involuntary turnover as they were involved in nearly every instance of presidential turnover. Boards directly determine whether many issues, such as financial controversy, athletics controversy, judgment, and of course, loss of board confidence meet the threshold of involuntary turnover. The case of loss of board confidence especially holds implications for boards. We did not attempt to place blame or responsibility for turnovers as a result of board confidence; clearly, loss of confidence can occur due to issues related to presidents, boards, or both. Regardless of who is responsible, however, trustees are ultimately responsible for judging the severity of problems facing a president. In the end, the findings of this study identify the key areas that threaten a successful presidential term and warrant substantial attention from the board should they arise.