Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin is joining Republicans in other states across the country in seeking to push professors to earn their salaries by teaching more. Walker cites raising college costs and a decrease in the among of time professors spend in the classroom. In today’s post, I am sharing a thoughtful piece by the Associated Press that looks at Walker’s proposal as well as similar efforts in other states. I provided background information and a quote to the story.

Republicans Press Professors to Spend More Time Teaching

By Todd Richmond

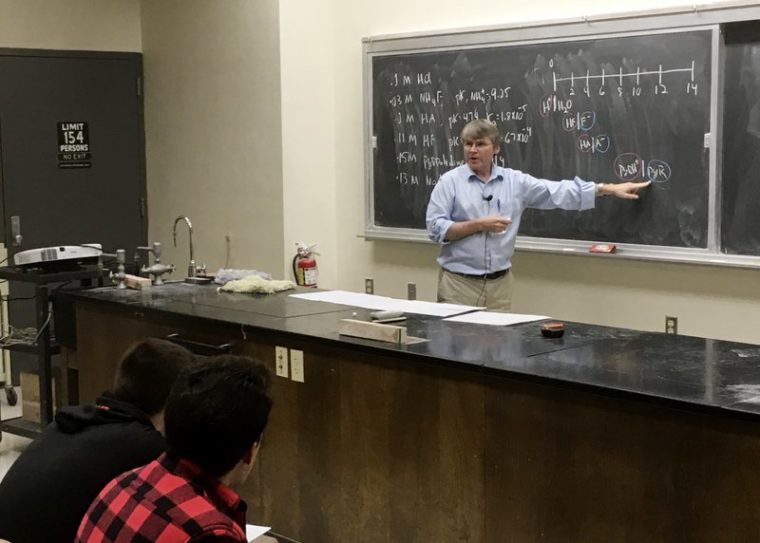

MADISON, Wis. (AP) — University of Wisconsin chemistry professor Robert Hamers has a jam-packed day ahead: an hourlong lecture, a conference call with colleagues about nanotechnology, meetings and plans to check on students in the lab.

With a workweek that he estimates often extends to 65 hours, Hamers is hardly lazy, but Gov. Scott Walker wants to make sure professors like him don’t neglect the classroom.

The governor has joined a national conservative push to get professors to do more teaching and less research. Provisions in his state budget proposal would reward faculty who spend more time in the classroom and make state aid to universities contingent on faculty instructional hours.

Republicans say they want to ensure undergraduates get enough bang for their tuition dollars. University officials say the GOP is trying to appease a base that’s suspicious of higher education in general, and they worry about pushing professors to deliver lectures instead of pulling in federal research dollars and seeking discoveries that reshape society.

“The idea that learning only takes place in a classroom setting is completely wrong,” Hamers said, calling it “an outmoded way of thinking.”

“What is more valuable?” he asked. Providing a lecture for 75 students or offering a two-hour, one-on-one interaction that a student remembers “for the rest of their life?”

It’s difficult to gauge how much time professors spend in classrooms across the country. The American Association of University Professors, the nation’s leading group representing college faculty, does not track classroom time, believing it’s not a good measure of productivity for faculty who might also do research, serve on committees or perform other administrative duties, said AAUP Research Director John Barnshaw.

The U.S. Department of Education has not looked at professors’ classroom time since 2003, when a survey showed that they spent about 58 percent of their time teaching, 20 percent in research and 21 percent in administrative work, personal growth or other activities. The survey has not been repeated because of budget constraints and lack of response, the agency said.

Faculty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison spent an average of six hours a week in the classroom in 2015, a time commitment that has held steady since 2000, according to data from across the University of Wisconsin system.

Walker’s 2017-19 budget would require UW regents to monitor faculty teaching loads, develop a standard teaching workload and reward professors for going beyond it. It would also give state aid to UW schools based in part on how they stack up against each other in faculty instructional time. That change could help the system’s four-year schools but cost research institutions such as UW-Madison and UW-Milwaukee.

“This is aimed at reversing a nationwide trend where professor time in the undergraduate classroom is down, while tuition has gone up about four times the rate of inflation since 1978,” Walker spokesman Tom Evenson said.

Walker has frozen Wisconsin tuition for the last four years. Evenson did not respond to an email asking if the governor’s office had any data supporting the assertion that classroom time is down.

Similar measures aimed at increasing professors’ classroom hours have been proposed elsewhere.

North Carolina state Sen. Tom McGinnis introduced a bill in 2015 that would have required professors to teach at least eight courses per year. It failed.

Ohio Gov. John Kasich’s last two state budgets have contained a provision requiring college boards to ensure faculty devote “a proper and judicious” part of their workweek to “actual instruction of students.” Kasich included provisions in two other budgets requiring full-time researchers to teach at least one more class per year. None of the proposals has passed.

In Idaho, Boise State University in 2012 adopted a policy requiring faculty to spend 60 percent of their time teaching.

UW system spokeswoman Stephanie Marquis said professors who focus on research can bring millions of dollars to the states, noting that Wisconsin students, faculty and staff secure more than 150 patents on new products and discoveries annually.

“My whole reputation is research,” said Laura Albert McLay, a UW-Madison associate engineering professor who specializes in improving efficiency. “The university wouldn’t run if we spent all our time teaching.”

She estimated that she put in about 50 hours in a recent workweek, with about half of that time spent teaching or helping students in her classes. The rest of her time is typically taken up with tenure and diversity committees and research with graduate students. Their projects have included developing mathematical models to help doctors prioritize patients and technology workers better protect their infrastructure.

Walker is trying to make college more affordable, she said, “but it’s important to have a real understanding of what professors do and what their lives are like. If a plan like this isn’t executed well, people will leave. There will be an exodus.”

Michael Harris, an associate professor of higher education at Southern Methodist University, said Republicans are simply trying to score points with supporters by forcing professors into the classroom.

“It’s just been a recurring theme for 10 or 15 years,” Harris said. “It’s red meat for the base. I would argue we want to look at the quality of instruction.”

Wisconsin’s Hamers estimates he spends about 16 hours a week lecturing, meeting with undergrads during office hours, preparing his lectures and overseeing students in the lab.

He spends another 16 hours in one-on-one meetings with students about their research projects. He invests another eight hours mentoring students in both his lab group and in a consortium of universities that are studying the effects nanoparticles from lithium batteries have on the environment. He also spends time overseeing Silatronix, a company he co-founded that researches how to make lithium batteries more stable with help from his students.

“Everything we’re doing with these students, that’s instruction,” he said.