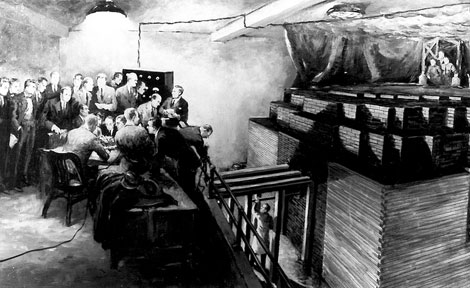

The deployment of nuclear weapons near the conclusion of World War II was not the first time technology influenced events on the world’s battlefield. Indeed, technological innovation has proved a constant ingredient in battle throughout the course of human history. However, the scientific success of the nuclear scientists working underneath the University of Chicago’s football stadium in 1942 ushered in an era of increased U.S. reliance on science and technology in the pursuit of national security. In today’s post, I will discuss the history of higher education in the post-World War II period related to national security, science, and research. In many ways, I believe this period set the foundation for how we have subsequently viewed higher education’s role.

The new reliance was based in part on the success of the partnership between higher education and the government during World War II. Many believed that public higher education could play an important role in the transition to peacetime and an economy without the benefit of massive wartime production.

This government interest in higher education led to the birth of a new type of institution which Clark Kerr termed the federal grant university. Describing the situation in higher education in this time, Kerr contends that “Currently, federal support has become a major factor in the total performance of many universities, and the sums involved are substantial . . . a hundred fold increase in twenty years” (Kerr 1963, 52-53).

It should be noted that this spending is limited to a handful of universities with Kerr’s own Berkeley as the most significant among the few public research institutions receiving a piece of the pie.

Additionally, the federal agencies whose appropriation institutions such as Berkeley increasingly relied upon were few. These agencies also tended to support research in limited areas believed to be important in protecting the country, which included the sciences, medicine, and engineering. Institutions that relied on these research dollars were often forced to spend an inordinate amount of capital and human resources in these areas in an effort to secure and maintain the federal funding even at the expense of other programs.

An even greater occurrence was the increased competition for these types of grants and other support that led to an explosion of Ph.D. programs and advanced research initiatives. This led to a decreased emphasis in many cases of undergraduate education during the enrollment increases as a result of the G.I. Bill.

These negative consequences held no weight in the wake of the 1957 launch of the Sputnik satellite by the Soviets. Congress redoubled their efforts and spending on U.S. research in an effort to beat the Soviet scientists and their early success.

This expansion provided some breadth in federal spending in some other areas that could help defeat the Eastern Bloc such as foreign language, but overall this spending was still limited in scope and breadth of institutional participation.

The Cold War is the first time in the history of public higher education that the federal government provided massive direct appropriation to colleges and universities in support of national defense.

Higher education responded to this intervention overwhelmingly as institutions sought to increase their research ability in order to compete with the few high-powered recipients of these grants.

Unlike the example of World War I, public higher education was not facing a financial crisis due to a drop in enrollment. To the contrary, the largest expansion of student access in the history of higher education was taking place with the G.I. Bill.

Nevertheless, colleges and universities cravingly sought and relied upon the federal research support.

The cyclical competition drove institutional decision-making. As spending in an effort to develop the research capability necessary to receive federal funds rose, the need for the funds to support the larger infrastructure expenditures subsequently rose.

In my view, this competition led to an arms race among institutions to increase their research and prestige in an effort to secure funding.

Higher education institutions continue to compete along these lines today, which may very well be distracting us for the advances that will help us win the next century.