In my History of Higher Education course this week, we were discussing the Yale Report and the reforms of the early 1800s. It struck me that so much of the debates during this period of American higher education mirror those we have today. In today’s post, I want to share a section from my monograph, Understanding Institutional Diversity in American Higher Education, that deals with this period. One of the values of studying the history of higher education is how often debates are recycled. I hope this gives you a new appreciation for some of the challenges that all of us in higher education are trying to figure out right now.

The early colonial curriculum largely focused on the ancient Latin and Greek languages. As the Revolutionary War approached, the curriculum remained focused on ancient languages, yet introduced Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke. Religion remained an overriding influence even as institutions struggled to incorporate Enlightenment philosophies. This tension remained through the early years of the new country, with Enlightenment ideals playing an increasingly greater role. Due to a lack of established faculty to teach the subjects, student unrest, and broader societal concerns, institutions slowly sought to reestablish the classical curriculum, moving away from the trend to increase professional education that started to occur in the early 1800s.

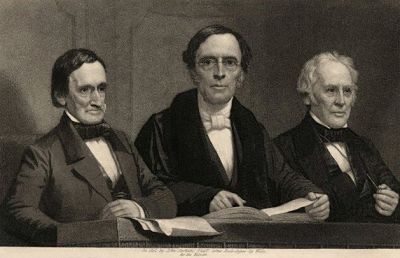

Reform efforts by George Ticknor at Harvard and Thomas Jefferson’s plan for the University of Virginia pushed defenders of the classical curriculum to reassert the supremacy of their views culminating in the greatest defense of the classical college— the Yale Report of 1828. In the report, Yale’s faculty clearly defined the purpose of collegiate education as “to lay the foundation of the superior education” (Yale Report, 1961, p. 278). The development of the discipline and furniture of the mind were best achieved through the classical curriculum. The Yale faculty argued that other forms of education such as professional training should be left to the work of other types of institutions. The Yale Report’s defense of the classical curriculum dominates curriculum discussions until the post–Civil War period. The emphasis on liberal education focused higher education on serving the limited, largely wealthy student population best suited to take advantage of this educational offering. The continuing emphasis on the value of liberal education remains a lasting impact of the Yale Report. Undergraduate education, particularly in elite higher education settings, focuses on liberal education eschewing vocational training. The emphasis on classical education serves as a significant counter- weight to critics arguing for concentration solely on career and vocational training. As each college and university finds the balance between these competing goals in line with their mission and student populations, a diverse array of curricular programs develop, which increases the level of institutional diversity present.

The Yale Report’s supremacy lasted until the Civil War and the enactment of the First Morrill Act creating land-grant colleges. While not calling for the exclusion of classical studies, the land-grant focus on agricultural and mechanical arts transitioned the debate toward the utility of practical education. Significant for long-term institutional diversity trends, the inclusion of traditional liberal education with practical fields of study within a single institution proves important in the development of American universities. In comparison, European institutions traditionally focus on either a classical liberal education or polytechnic studies (Trow, 1987). While the ascendancy of the American university would not occur until close to the turn of the century, the legacy of the Morrill Act sets the foundation for the complex “relationship between advanced learning or graduate education, and the American college” (Geiger, 2011, p. 51). Fundamentally, the second half of the 19th century saw American higher education institutions responding to the challenges presented by evolving social and economic contexts. The addition of new students and academic offerings augmented the traditional approach of higher education while laying the groundwork for the university building and emphasis on research that was about to begin.