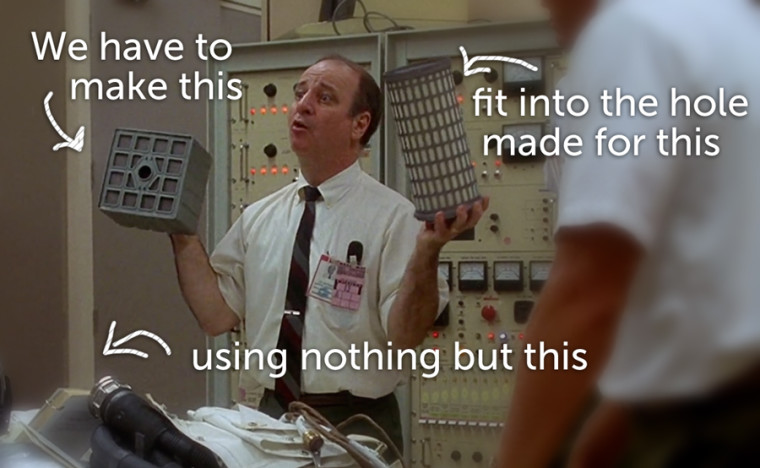

When I work with faculty on improving their teaching, one of the areas that I constantly try to get them to improve is in their lecturing. Particularly in certain disciplines, lecturing is the primary instructional approach used by professors. Lecturing is probably the oldest teaching approach and can be effective. However, lecturing can also be done very poorly as the stereotype of the professor reading form the yellowed lecture notes illustrates. I try to convince faculty to include more active learning approaches into their classes and I find the pause procedure is an excellent vehicle for this. In today’s post, I want to share an excerpt from my book on college teaching (Teaching for Learning) that describes the pause procedure and how to use it effectively in the college classroom.