Today, the United States celebrates Labor Day. For over 100 years, Labor Day has served as an opportunity to honor the role of labor and workers in our society. Of course, it more often signifies the end of summer with a last chance for grilling, boating, and swimming. In the real tradition of the holiday, it seems appropriate to consider the current state of adjuncts in higher education. We have seen a tremendous change in the working status and condition of faculty over the past generation. No where is this more obvious than the current state of adjuncts.

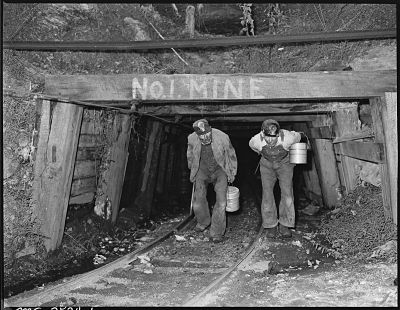

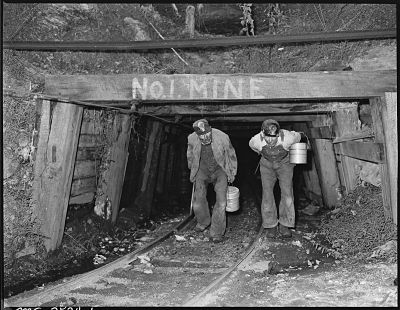

Photo credit: National Archives

Faculty are the core of our nation’s colleges and universities. The institution exists for faculty to education and train students. Most higher education institutions have a three part mission of teaching, research, and service. Who primarily performs these functions? The faculty.

The changing landscape of faculty represents one of the biggest changes impacting institutions from the most prestigious Ivy League university to the smallest technical college. In particular, four ideas deserve consideration.

1. Cost savings haven’t gone to lower student costs, but to cover administrative growth.

Education is a labor intensive process. Faculty and staff are the greatest expense for a campus. Thus, reducing the cost of faculty should reduce the cost of higher education. This argument is one of the primary ones for increasing the use of adjuncts.

In 1975, according to the American Association of University Professors, full-time tenured or tenure track faculty comprised 45.1% of the instructional staff in higher education. In 2009, this number had shrunk to 24.4%. What happened?

Universities put the focus on hiring part-time faculty. Over the same time, part-time faculty grew from 24% to 41%.

You will often hear the narrative that faculty salaries are the cause of the escalating costs of higher education. This simply isn’t true. And even if it was true a decade ago (it wasn’t), the emphasis on part-time faculty reduced instructional cost.

While there have been cost savings by focusing on part-time faculty, this savings has been more than swallowed up by the growth of administrative positions. Since 1976, the number full-time nonfaculty professionals has more than tripled.

Now, I work in a higher education administration program. Most of my students take these positions. I also believe many of these people improve the education we offer our students. However, the hyper-professionalization and a complex regulatory and legal environment grew these numbers far more than necessary educationally.

One has to ask if we would be better off lowering the cost for students or spending more of our full-time employee budget on faculty.

2. We know little about the impact on student learning.

We simply do not know enough about what impact the growth of adjuncts has on student learning. Some studies find that students perform worse and others suggest there is no difference when accounting for the fact that adjuncts teach more remedial and part-time students.

It is clear that the use of adjuncts is much higher in less wealthy institutions. I worry about the circumstances for instruction at these institutions which rely so heavily on adjuncts. An instructor that is balancing teaching gigs from many institutions, students trying to work full-time while raising a family, and an institution struggling financially seems to be a perfect storm. I wouldn’t be surprised if learning under these circumstances suffered.

This isn’t the fault of adjuncts or their students, but of a society that fails to provide sufficient resources to facilitate success.

3. Effective campus governance requires full-time faculty and especially tenured faculty.

One of the biggest concerns I have for the growth of part-time faculty is the impact on campus governance.

Faculty serve as an important player in shared governance’s checks and balances system. Who serves on curriculum committees? Who criticizes a poor administrative decision? Who advocates for the teaching and research function? Even if you aren’t a fan of shared governance, who writes the graduate school recommendations?

Full-time faculty play a critical role in campus decision-making. You can replace this voice with others, but I believe this leads to poor decisions in both the short and long run. Yes, faculty can be a pain and debate for too long. However, the faculty voice is important to making sure the university considers alternatives and as a check on decisions that can hurt the institution or students.

Tenured faculty are empowered and best able to serve this role thanks to the protections of tenure. In fact, this is a major reason why faculty need tenure. At the other end of the spectrum are adjunct faculty that are largely unable to fill this role. Whether because they are balancing multiple classes and institutions, other full-time careers, or concerned about their next contract, adjuncts simply can not effectively play this role on campus.

We need full-time faculty and particularly tenured faculty to ensure effective campus governance. The growth of adjuncts and the decline of tenured and tenure track faculty should be cause for great alarm.

4. The working conditions for many adjuncts are unconscionable.

On Labor Day of all days, we should pause and consider the circumstances of many adjuncts in higher education.

These people are well educated and have great potential to offer colleges and universities as well as society. Yet, their working conditions are deplorable.

No, they aren’t working in a factory with poor air quality or in a mine without proper safety checks. However, colleges and universities—intentionally or not—are taking advantage of these workers.

Many adjuncts do not receive the resources to survive, much less thrive, professionally or personally.

Professionally, adjuncts may receive their contracts late allowing little time to prepare for class. They may not have offices on campus to hold office hours. They may have no access to administrative support. They receive little by way of professional development. One of the first steps that I took upon becoming the director of our teaching center was to invite adjuncts to our teaching effectiveness symposium. It was a small step, but an important one. We must do better to help our adjunct instructors deliver the best education possible.

Personally, adjuncts are forced to cobble together a series of contracts from several nearby institutions. This turns them into road warriors running between campuses trying to cover as many classes as possible. They receive a couple of thousand dollars per class with no benefits. With the decline of full-time teaching positions, many have little prospect for full-time work and may ultimately be forced out of higher education.

Added to something, typically in an auxiliary way.

I’m normally loath to use a word’s definition to make a point and usually do not allow my students to do so either. I am making an exception in this case because it is so clear. The adjective adjunct means something that is added typically in an auxiliary way. Adjunct instructors can play a powerful role in higher education as supplements. Whether a CEO coming to a business school to teach a leadership class or an engineer teaching about a particular new technique, adjuncts can provide additional expertise as a supplement to the instructional faculty. However, adjuncts should not be used a replacement for the faculty.

I take vitamins as a supplement to my diet. This helps me in areas where I may be deficient and to improve my overall health. I couldn’t stop eating and just take vitamins. This doesn’t mean the vitamins are bad for me or my health. I just can’t use them to replace something that is central to my health- a well-balanced diet.

The way higher education uses adjuncts today is wrong. Not only are we ignoring a well-balanced approach to faculty and instruction, but we aren’t treating our adjuncts with the respect and dignity they deserve.

As you grill your hamburgers today and celebrate the end of summer on this Labor Day, take a moment to consider the plight of the adjunct.